- Home

- Kane, Paul

The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy Page 3

The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy Read online

Page 3

Cenobite concept sketch for Hellraiser (courtesy Clive Barker).

Displaying definite expressionist and surrealist tendencies, as one would expect after the group’s exposure to film societies in the area, the movie also boasts some unique visual parallels with Hellraiser. We pass through a doorway, for instance, and a strange light sheen gives the frame an unreal quality. Taylor very closely resembles Kirsty with her long, dark hair, white smock and black-stained eyes. Then there are the requisite candles (present in both Kirsty’s dream sequence and at Frank’s puzzle-solving near the beginning). And the resemblance between Herod and the bearded Keeper of the Box is uncanny.16 But most intriguing is the first cinematic use of a kiss as a betrayal, in addition to Taylor’s scratching of a cheek, which Kirsty recreates when Uncle Frank is pretending to be her father.

Cenobite concept sketch for Hellraiser (courtesy Clive Barker).

Yet more similarities abound in a second short, The Forbidden (1975–78). This is probably not that surprising, as it was based loosely on Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, Barker’s preferred reworking of the Faust myth. Funded by £600 from Merseyside Arts, this time the footage was shot in negative on 16mm black and white stock, but stood for quite a while before being put together. The first thing to say is that The Forbidden plays very heavily on an obsession with puzzles and games. The opening shots are bare feet on a chessboard floor, while the odd symbols painted on paper and put together like a jigsaw puzzle recall the sides of the Lament Configuration box itself. Hand animated birds flutter behind a grid, trapped like the birds at the pet shop where Kirsty works. And there is a gridded piece of wood with nails at each intersection.

Talking about this, Doug Bradley recalls:

Clive had built what he called his nail board ... and spent endless hours playing with what happened if a light was swung around in front of it to see the way the shadows of the nails moved and what happened if it was top lit and so forth. Of course, when I saw the first illustrations for this gentleman [Pinhead] it rang a bell with me—that here was actually Clive putting the ideas that he’d been playing around with, with the nail board, in The Forbidden. Now ten to fifteen years later or whatever, here he’d actually put the image over a human’s face, which is typical of the way he works.17

But undoubtedly the most recognizable factors are the Angels at the end—robed figures who inflict pain—and the figure of Faust himself once he is skinned. Peter Atkins played him in full make-up, actually strips of paint that were peeled back revealing new layers of flesh and muscle. When viewed in negative and for the amount of money available, the results are shockingly effective and would prove to be Barker’s first ventures into making less look like more. Owing much to those Vesalius pictures, Faust’s character is a distinct antecedent to skinless Frank Cotton in Hellraiser, and those torturing him can only be equated to the Cenobites.

Cenobite concept sketch for Hellraiser (courtesy Clive Barker).

These same preoccupations would resurface when Barker wrote The Hellbound Heart novella almost a decade later. Originally published in 1987 as part of the Night Visions 3 anthology—alongside stories by Ramsey Campbell and Lisa Tuttle—the tale is prefixed by a quote from John Donne’s Love’s Deitie (“I long to talk with some old lover’s ghost, Who died before the god of love was born.”) and differs from the finished Hellraiser in a number of ways.

First, we are provided with more explanation about the puzzle box itself: created by a Frenchman called Lemarchand, a “maker of singing birds.”18 Later this would form the genesis of the fourth movie in the series. Second, the Cenobites are given a definite back history: referred to as “the order of the Gash,” hinted at in the diaries of Bolingbroke and Gilles de Rais.19 They are more conversational and far less imposing than their cinematic counterparts. During the hospital confrontation with Kirsty, one muses, “We’d better go.... Leave them to their patchwork, eh? Such depressing places.”20 The figure we would come to call Pinhead is here asexual, bordering on female: “Its voice, unlike that of its companion, was light and breathy —the voice of an excited girl.”21 And the Engineer creature, in the film a fleshy, noisy mass with rows of teeth, hovers at the edge of the action and only intervenes to whisk a dying Julia off at the end and then pass the box back to Kirsty. Their lines are not quite as polished, either. Compare, “Maybe we won’t tear your soul apart” with the immortal tagline everyone knows from the film.

Night Visions, the original anthology featuring The Hellbound Heart (Arrow Books).

The female protagonist, Kirsty, is the friend, not the daughter, of Rory Cotton (renamed Larry in the film), a fact which holds great significance when exploring the relationship between these two characters, as well as the family dynamics we will come to later. She is also, to quote Barker, “A total loser. You can live with someone like that for the length of a novella. You can’t for a movie.”22 Even her body works against her as Frank is chasing her through the house at the climax: “Swallowing the breath her cry had been mounted upon had brought an unwelcome side-effect: hiccups. The first of them, so unexpected she had no time to subdue it, sounded gun-crack loud.”23

Also, Frank appears to Julia the first time through a gap in the wall: a more traditional shade haunting the upstairs “damp room,” able to maintain his substance only for a short time. And he is brought back not simply by the blood, but by route of leaving his spilled seed on the floor. The murder weapon of choice for Julia in this novella is a knife, and Frank uses bandages to cover his regenerating skin, a homage to the Mummy films Barker so admired when he was growing up (this image would be adopted by a skinless Julia in Hellbound: Hellraiser II). Most of the changes made to the story at script level can be understood perfectly from a visual point of view. It makes for better cinema to have Pinhead speaking with a deep, booming voice, or to have Julia wielding a hammer and being splattered with blood, or even a skinless Frank walking around in his far less clichéd shirt and suit.

As is to be expected in a work of prose, Barker delves deeper into character backgrounds and motivations. We learn exactly how Frank came to be in possession of the box, for instance. While smuggling heroin in Düsseldorf he’d come across the legend again, which led him to a German called Kircher, who in turn could get him the box. “The price? Small favors, here and there. Nothing exceptional. Frank did the favors, washed his hands, and claimed his payment.”24 Not only that, Frank’s experiences after he has opened the box are much more internalized. We’re given passages about how the Cenobites heighten his senses: his touch, sight, sound, everything magnified to make the best use of his suffering. “It seemed he could suddenly feel the collision of the dust motes with his skin. Every drawn breath chafed his lips; every blink, his eyes. Bile burned the back of his throat, and a morsel of yesterday’s beef that had lodged between his teeth sent spasms through his system as it exuded a droplet of gravy upon his tongue.”25 And, of course, his true feelings about Julia are made more explicit: “He remembered her as a trite, preening woman, whose upbringing had curbed her capacity for passion.”26 We even find out more about Julia’s victims, something which had to be achieved with the shorthand of dress and dialogue in the film.

The basic story line remains the same from The Hellbound Heart to Hellraiser, however, and regardless of the fact that Barker claims he never wrote it with a movie in mind, the novella has a very resolute three-act structure. It is set in a limited—even claustrophobic—handful of locations, with the ordinary house on Lodovico Street playing host to much of the gruesome action. And there is only a quartet of characters at the very kernel of the story: Rory, Julia, Frank and Kirsty. Whether he did it consciously or not, in The Hellbound Heart Barker fashioned the ideal template for a low-budget horror movie. Now all he needed was a way to get that movie made.

At first, Barker thought about shooting the project with his friends on Super 8 or 16mm. Then, by chance, he was introduced to Christopher Figg through an old Dog Company friend, Oliver P

arker. Figg, an assistant director on pictures such as The Dresser (Peter Yates, 1983) and A Passage to India (David Lean, 1984), was now interested in producing a horror film. Still very inexperienced, Figg joined forces with Barker and they were given some start-up money by Oliver’s brother. Next they put together a package containing a number of Barker’s conceptual drawings and a draft version of the script. Armed with these they flew out to L.A. to find backers. New World Pictures, founded by B-movie director Roger Corman (famous for his Poe adaptations in the 1960s) offered them a $4.2 million budget; not an inconsiderable amount for a first time director with hardly any footage under his belt. Suddenly Hellraiser was about to become a reality.

Work began gathering cast and crew, and with the help of his fellow producers, David Saunders and Christopher Webster, Figg assembled a technical dream team for Barker. To start with, there was the director of photography, Robin Vidgeon, with twenty years of experience. Vidgeon had worked as an assistant cameraman on films like Rollerball (Norman Jewison, 1975) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (Steven Spielberg, 1981), and, like Barker, was a fan of the Italian horror films of Dario Argento. This explains why some of the lighting set-ups very closely resemble scenes from Suspiria (1977) and Inferno (1980).

Then came production designer Mike Buchanan, responsible for the film’s décor and set construction. He secured the location house in the suburban district of Dollis Hill, North London, where most of the filming would occur (it was rumored someone had gassed themselves in the garage) and the stage at Cricklewood’s Production Village—only a few minutes away—which would double for the opening bazaar and attic room. In charge of special effects were Bob Keen, Geoff Portass and Image Animation. Keen came fresh from triumphs on such movies as Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983) and Highlander (Russell Mulcahy, 1986), although it was his first time as effects supervisor.

In terms of casting (with the aid of casting director Sheila Trezise), young German-born actor Sean Chapman was chosen to play the part of Frank Cotton. Chapman had made his screen debut in Leidenschaftliche Blümchen (André Farwagi, 1978) and Scum (Alan Clarke, 1979) and landed TV work in the aborted Dr. Who spin-off, K-9 and Company (1981), before appearing in the ill-fated Underworld. His look was totally right: dark, brooding and charming. And his initiation into the world of Hellraiser was to hang upside down from chains for a test shoot until he threw up, footage of which was used in the flashback sequence where skinless Frank recounts his tale.

Meanwhile, British actress Clare Higgins came on board as Julia, having had a little experience of wayward women roles playing parts like Stella in A Streetcar Named Desire onstage. Higgins had also carved a name for herself in various BBC television serials—Pride and Prejudice (1979), The Citadel (1983)—and debuted on the big screen in Hugh Brody’s feature film 1919 (1985). The attraction for her was plain: “I’ve done all the nice parts, but I love playing Julia because she’s so evil. There’s a great range to the part: I go from being bored and domestic to being absolutely vile....”27

Fresh-faced American actress Ashley Laurence became involved with the film after she got a phone call from a friend who was PA-ing at New World, and who was also in her teenage drama workshop. Barker and Figg had auditioned a number of actresses for the role of Kirsty, but couldn’t find one they wanted. So when they traveled from New York to Los Angeles, Laurence had a chance to impress them. Recalling her first encounter with Barker, Laurence says: “I didn’t know what the script was about. I didn’t know anything. I met him [Clive Barker] and he was really enthusiastic and he was really communicative, and he said to me, ‘Okay, your Uncle Frank is in your father’s skin and he wants to kill you and have sex with you. Tell me how you feel about that.’”28

Barker, too, has warm memories of Laurence’s audition, claiming she could outscream Fay Wray,29 and didn’t mind looking grimy. It also helped that she resembled Jessica Harper, star of Argento’s Suspiria, who also spent much of that movie in a state of perpetual disarray. Moreover, both Barker and Figg recognized a feistiness about the cinematic newcomer, something that would translate well in her scenes with Frank, Julia and the Cenobites. Here was someone who, unlike her literary counterpart, would fight back, who would carry on the tradition of the tough female heroine from horror films of the late ’70s and early ’80s, typified by Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley.

The most famous member of the cast, and a real coup for the production, was well-known U.S. actor Andrew Robinson. In the two years before Hellraiser, audiences had seen him starring alongside Cher in the moving film Mask (Peter Bogdanovich, 1985), and opposite Sylvester Stallone in the action movie Cobra (George P. Cosmatos, 1986). But he was probably still best known at that time for his debut role in Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971) as the lunatic rifleman Scorpio. Robinson took a huge gamble flying over to star in this film; not only was it in the horror genre, with everything that implied, it was also being directed by a novice. Fortunately, after reading the script he was very impressed and liked the idea of being able to play both the mild-mannered Larry and his demented brother Frank.

His presence added extra credibility to what was already becoming much more than the average shocker, and he improvised some classic moments in the film (Frank readjusting his eye; his last line, the shortest verse in the Bible: “Jesus wept”). Speaking about the film as part of an electronic press kit for New World, Robinson said, “I think the movie is unique within the genre. I think the images, especially the images of horror, are unlike anything anybody has seen. I think it’ll be a bizarrely fascinating film. There’s no middle ground. They [the audience] will either loathe it or go out of their minds about it. But at least they’ll have a reaction to it.”30

When it came to roles for the Cenobites, the director selected actors who were closer to him. Bedfordshire born Simon Bamford had been attending North London’s Mountview Theatre School when he met Barker for the first time: “I met Clive through a friend of mine who I was sharing a house with at the time. Clive was doing one of his horror plays and this friend was making some specialist props for him. That’s how I got introduced to him. We became good friends and then he asked me to join his company.”31 He played with the Dog Company for about a year and a half before they disbanded, and then went on to do other theater work. He rang up out of the blue to see what Barker was working on and it just so happened that his call coincided with this project. Barker told Bamford about Hellraiser and offered him the Butterball role there and then.

Nicholas Vince was also a Mountview student and used to live around the corner from Barker, who saw the actor in some of his drama school shows and liked his performances. “He and I met up at a party over a cup of coffee and said, ‘We must work together sometime.’ And it took us six years!”32 That turned out to be as the Chatterer Cenobite. For the Female Cenobite, Barker enrolled his cousin, Grace Kirby, whose only previous film role had been as a French teacher in Heavenly Pursuits (Charles Gormley, 1985).

But when it came to the part of Lead Cenobite, Barker turned to his old school friend and a Dog Company player, Doug Bradley, although he gave him the option of playing one of the removal men with the mattress. “It seems odd to me now, but I very nearly settled for the latter. This was going to be my first movie, so why would I want to be buried in latex? Who would be any the wiser? Much better to make the briefest of appearances and be seen.”33 After much deliberation, and assuming he’d drawn the short straw, Bradley plumped for the Cenobite and let Oliver Parker have the other part.

The requirements for skinless Frank were a little more exact. They needed an actor who was thin enough to wear the muscle-coated bodysuit. Step forward Oliver Smith, who had starred in the Jesus of Nazareth miniseries (1977). As with the Cenobite roles, the actor also had to be comfortable spending up to six hours in make-up getting ready before the cameras even started rolling: “The main body was prefabricated around my form, so I got into that for each morning’s work. So the head was done bit by bit each mo

rning.... Bob Keen and Cliff Wallace [the personal creator] whacked on several sections of thin rubber. It was a grueling process, glue and gunge.”34 And those cameras actually began rolling towards the end of 1986 when Hellraiser was made over a nine to ten week period (seven weeks initially, extended by New World), under Barker’s tongue-in-cheek alternative title Sadomasochists from Beyond the Grave.35

Most of the cast remember the shoot with affection, especially Barker. Speaking about it in the introduction of The Hellraiser Chronicles, he comments: “I think back to the making of Hellraiser with unalloyed fondness.... The cast treated my ineptitudes kindly, and the crew were no less forgiving.”36 It was certainly a steep learning curve for someone who admitted that when he first started out he “didn’t know the difference between a 10-millmeter lens and a 35-millimeter lens. If you’d shown me a plate of spaghetti and said that was a lens, I might have believed you.”37 Luckily, as he remarks, the cast and crew were supportive, and showing his efforts to the producers was a major incentive to get things right.

On a set visit, Tim Pulleine of Films and Filming had this to report about the director firsthand.

Certainly Barker, affable and unassuming behind his designer stubble, seems very much at ease on the set as he rehearses and blocks out part of a scene between Oliver Smith and one of his intended victims. “Keep squirting to the last minute,” he cheerfully adjures the make-up man who has been spraying a glistening substance onto Smith’s cranium to make him look more awful than ever.38

Undoubtedly, the fact that cast and crew were all living in close proximity to each other, some in the location house itself, gave the shoot a communal feel that harked back to the days of the Dog Company. Perhaps this accounts for why Barker relaxed into his stride so quickly. He knew how to deal with actors, he knew how to tell stories visually; all that was lacking was the technical expertise, which he picked up as the production progressed.

Pain Cages

Pain Cages Nailbiters

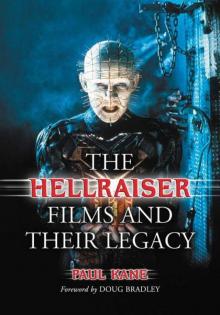

Nailbiters The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy

The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy