- Home

- Kane, Paul

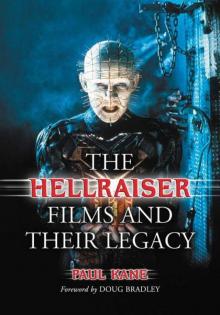

The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy Page 2

The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy Read online

Page 2

As a child, Barker was also obsessed by a book on anatomy by Andreas Vesalius, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543). Its pages depicted skinless figures in delightfully graceful poses. “They’re very meticulous, neoclassical,” Barker once commented, “...and these are very beautiful etchings in which you get flayed men and women standing in classical poses or leaning against pillars. The whole atmosphere of these pictures is cool and elegant and beautiful.”2 This contrast between the repugnant and the resplendent would infuse many of his pieces in years to come.

Barker lived on Oakdale Road, near Penny Lane, in an ordinary house with four bedrooms—his was at the top of the stairs—and, yet, extraordinary, forbidden things occurred inside. Here he read such landmark horror books as Frankenstein (Mary Shelley, 1818), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Robert Louis Stevenson, 1886) and Dracula (Bram Stoker, 1897) and devoured the works of M.R. James, Arthur Machen, and Edgar Allan Poe, who became a particular favorite. Indeed, the first horror book he ever read was Tales of Mystery and Imagination which had a lurid front cover featuring a skull, a red sky and an old dark house. He also began to stretch his imagination, particularly through art—a quality he picked up from his parents, who were both decent artists.

But it was at Quarry Bank School that this talent started to seep out in various ways, particularly via the plays he wrote and organized. His art teacher at the time, Alan Plent, has mentioned seeing Barker walking through the corridors with a mock severed head to promote a play he’d written.3 His reaction against the mundane, official plays that were being performed at the school, these productions also brought him to the attention of friends and collaborators like Peter Atkins and Pinhead-to-be Doug Bradley. This group, led with passion and verve by Barker, formed the nucleus of Hydra Theatre, and would finally evolve into his fringe theatre group, the Dog Company.

After leaving Liverpool University with a BA (Hons) in English literature, Barker and the Company went on tours giving performances of plays like Dog (1978), Nightlives (1979) and The History of the Devil (1980), all penned by Barker and following the tradition of Grand Guignol theatre (see Chapter 4). The latter clearly displays a certain fixation with all things hellish and biblical, though here Lucifer stands trial to decide whether he is eligible to return to heaven. Doug Bradley actually played the Devil in the original production, but his portrayal was very different from the Cenobites of Hellraiser. In truth, some of the dialogue spoken when he is being cross-examined displays more of a connection to Frank’s character than anything. Here he talks about his travels to distant regions on earth after he was cast out: “I was a student of the world, sir, and something of a sybarite. I wanted to taste every pleasure. I’d been a while in Athens and I’d heard of these towns on the very edge of the civilized world.”4

Page from De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Andreas Vesalius (1543).

It was around this time that Barker began to write short stories to amuse his friends in the Dog Company, now based firmly in London. These stories grew into the first volumes of his popular Books of Blood, published in England by Sphere in 1984. Intelligent, yet uncompromising in their graphic nature, these stories also contained many of the seeds for Hellraiser. In the first story, for instance—“The Midnight Meat Train”—we are witness to the results of brutal killing: “It filled every one of his senses: the smell of opened entrails, the sight of the bodies, the feel of fluid on the floor under his fingers, the sound of the straps creaking beneath the weight of the corpses, even the air, tasting salty with blood.”5 Not a far cry from the slaughterhouse created by the Cenobites at the opening, or even by Frank and Julia.

Then there are the notions of existence and love beyond death rendered in “The Forbidden” (later filmed as Candyman, Bernard Rose, 1992). Here a woman searching for the roots of an urban myth about a hook-handed killer discovers that her fate is inexorably linked to his, and that her love for this fiend overwhelms what he might actually be—definitely a common motif in Barker’s stories.

The characters in Books of Blood very often fall in love with monsters in spite of, or more commonly because of, their physical appearance. The children in “Skins of the Fathers,” for example, are the result of communion between the town’s women and what can only be described as creatures beyond our understanding, although the real monsters turn out to be human (a theme Barker explored more fully in his book Cabal, filmed as Nightbreed). On a different tack, it is the base urge rather than emotion that is highlighted in “The Age of Desire,” where a scientist’s experiments imbue his subject with pure, unadulterated lust pushed way beyond its limits.

Also relevant is the way Barker approaches “the flesh” and its malleability in stories like “Jacqueline Ess: Her Will and Testament” and “Confessions of a Pornographer’s Shroud.” As Michael A. Morrison points out in his study, “Monsters, Miracles and Revelations,” “In his [Barker’s] tales the easy mutability of the human form opens up the possibility of rebirth, at least for those willing to face his myriad marvels, mysteries, and monsters.”6

Finally, we have the appearance of demons bound by the laws of Hell in “The Yattering and Jack” and “Hell’s Event.” In the former their breakage forces the nuisance demon Yattering to become a slave to his victim; in the latter, failure to win a race means that the Earth is “safe” for another 100 years. Their summoning is also depicted by way of the solving of a knot-puzzle in “The Inhuman Condition.” This last idea is an extremely close precursor to the one in Hellraiser—simply exchanging rope for the puzzle box—and also dwells on the obsessive tendencies of its solver:

And still the knots. Sometimes he would wake in the middle of the night and feel the cord moving beneath his pillow. Its presence was comforting, its eagerness was not, waking, as it did, a similar eagerness in him. He wanted to touch the remaining knots and examine the puzzles they offered. But he knew that to do so was tempting capitulation: to his own fascination; to their hunger for release.7

Running parallel to these fixations are the doorways that open up, revealing other realities that exist alongside our own—much like the city shown to the prisoner as part of the story “In the Flesh.”

Even more telling, though, was Barker’s first full-length, and arguably only, horror novel, The Damnation Game (1985). In this, Barker reworks a favorite story of his, the Faustian fable (see Chapter 2) through the eyes of Marty Strauss. Paroled from prison, this character has already paid a high price to feed his gambling addiction. But when Marty is hired as a bodyguard to rich businessman Joseph Whitehead, he discovers his boss has made an even more dangerous bargain with the deadly Mamoulian, the embodiment of our own guilt and desire. The power of love is again touched on as Marty falls for Whitehead’s daughter, Carys, but it is that central relationship between Mamoulian—to all intents and purposes the Devil figure, even though we discover he is nothing of the kind—and his victim that is of interest to students of the Hellraiser saga.

What’s more, there can be no denying that both The Books of Blood and The Damnation Game have a definite cinematic quality to them. In fact, Barker’s short story “Son of Celluloid” relies inherently upon cinematic inspirations and icons. This is probably why fellow Liverpudlian and horror author Ramsey Campbell drew the comparison in a letter to Sphere about Barker: “He’s the first writer to write horror fiction in Technicolor—the first to take the gruesome horror movie and make it work as prose.”8 The author has made no secret of his love of cinema in all its forms, and it was an early encounter at age fourteen with Hitchcock’s Psycho that showed him how this medium could be used to its full advantage. After sneaking in to see it with a friend, Barker caught the ending, where Mother Bates’s skeleton is found in the basement. Once he’d got over his initial fright, he waited around for it to play again and observed the reaction of four girls watching: “I remember thinking quite distinctly, ‘I am in control this time, because I know what’s going to happen. And these poor creatures in front of us don’t.’”9 Renaissance m

an that he is, it could only have been a matter of time before he turned his attentions to horror films himself. And that time was fast approaching.

Books of Blood front cover (courtesy Clive Barker/Sphere).

Speaking in an interview with Fangoria in 1986 after the Books of Blood had been released in the U.S., Barker revealed that he had recently returned from Hollywood, where he had been pitching story and novel ideas to studios like Columbia and Paramount. He also told the magazine he’d written one original screenplay for a movie called Underworld (a.k.a. Transmutations), and had been working on another for a film based on one of his shorts, Rawhead Rex.10 Barker’s association with the director of both these films, George Pavlou, began in 1982 when the pair met at a dinner party. At that time London International Film School graduate Pavlou had only helmed a few TV commercials and short films, and had served as second unit director on the British-based episodes of Hart to Hart. Understandably he was keen to direct a feature of his own, and asked Barker to write a synopsis. This Barker did, once again pre-empting the themes of Nightbreed, that of monsters living in a clandestine community.

The twist here was the film noir/horror cross fertilization—or as Barker succinctly put it, “Gangsters vs. Mutants”11 and this eventually attracted financing (under £1 million) from U.K. producers Green Man in 1984, who also optioned five of Barker’s stories from the Books of Blood. Unfortunately, the money was only available if they started straight away, without a full script. Filming on Underworld began in 1985 at Limehouse Studios (who were co-producing the film), with Barker on hand during principal photography to do the necessary rewrites. But as shooting went on, James Caplan was hired to redraft the screenplay. Caplan cut out over half of Barker’s dialogue and replaced it with clichéd gangster speak. The result was a disjointed story, doomed right from the start.

While the set designs by Len Huntingford (lit by Sidney Macartney’s cinematography) are impressive, and notable British actors Denholm Elliott and Stephen Berkoff deliver entertainingly hammish performances, the rest of the cast are wooden in the extreme. Pavlou’s visuals are more MTV than Dario Argento or David Cronenberg, as he claimed, and it was later discovered that the producers had come up with funding by telling potential backers that it would be an hour and a half rock video! The real tragedy, though, was a missing scene Barker scripted in which Elliott’s Dr. Savary, who has been using hypodermic needles on people throughout the film, has his face punctured by dozens of them, a familiar image to Hellraiser fans. Instead, Savary gets set alight because it was the much cheaper option.

After filming was completed, there followed a long battle to try to secure a distributor. Finally a deal was struck with Empire Pictures from the U.S., Charles Band’s company. Empire trimmed the movie by almost ten minutes to make the pace faster and renamed it Transmutations. They gave it a limited release, with no promotion whatsoever, so it died at the box office. The film appeared, with the cut footage restored, on Vestron Video the following year.

But worse was yet to come. In spite of this catastrophe, Green Man ploughed ahead with a version of Rawhead Rex, one of Barker’s most popular short stories. And although he hated what they had done with Underworld, the writer listened to what his producers had to say. “When Kevin Attew (of Green Man) asked me to write the script for Rawhead Rex, we had a couple of exchanges that went something like, ‘We know we fucked up the first one because we didn’t concede the fact that it was a horror movie.’”12 After being assured that they’d leave the horror in this time, and that he would be given a greater amount of control over the project, Barker produced a first draft screenplay.

The location had to be shifted from England to Ireland for funding reasons, and the lead character—originally an ad executive—was turned into an American university professor visiting to research pre–Christian burial sites with his family. The Winds of War actor David Dukes was drafted in to play the lead, while Kelly Piper, whose previous roles had included a nurse in Maniac (William Lustig, 1980) and a prostitute in Vice Squad (Gary Sherman, 1982), signed on as his wife. Meanwhile, the crucial job of creature effects was given to Peter Litten’s Coast to Coast company, who would have to commute from their studio in Britain. The seven-week shoot began in County Wicklow, Ireland, in February 1986. However, once filming commenced, Barker wasn’t even allowed on set and alterations were again made without his say. As the budget dwindled from $3 to $2 million, fears rose that this film would turn out like the last.

If judged as a straight piece of horror entertainment, Rawhead Rex isn’t the worst movie you’ll ever see. There are even some resemblances between the early parts of John Landis’s seminal An American Werewolf in London (1981) and Rex, certainly when it comes to the rural setting and the sense of outsiders invading a tight-knit community. The film cleverly draws on the opposites of Pagan and Christian standpoints for its central conflict, which can also be extended to the ideas about unbridled desire and rage versus goodness and faith. This is complemented by solid performances from Piper and the late Dukes, whose outbursts after his son is murdered are emotionally draining to watch.

What fetters the movie is the Rawhead creature itself, which deviates quite markedly from Barker’s original vision of a ten-foot phallus on legs (see Les Edwards’ graphic novel adaptation for a better idea of what Rex should have looked like). This is crucial for the payoff to work, where we discover that Rex is scared of women, more specifically female genitalia. It explains the creature’s adverse reaction to pregnant females throughout the story and film, and, more importantly, how he is defeated. The loss of this subtext drags the movie down to the level of a simple monster-on-the-loose flick, which is, sadly, how Attew viewed the concept: “It’s Jaws on land ... purely an updated ’50s B movie.”13 In all honesty, Litten’s Rex looks like some kind of weird gigantic monkey with a punk haircut.14 Working with very little to go on, and with only six weeks of preproduction afforded to him, he came up with a one-piece suit for the gigantic German commercials actor, Heinrich von Buneau—which he had originally intended to be a twenty-piece prosthetic—and an animatronic head with fifteen facial movements and glowing red eyes for close-ups. With the right lighting setups and editing, they might have worked, but, unlike the shark in Spielberg’s classic or even the Alien in Ridley Scott’s 1979 classic of the same name, Rex spends far too much time on-screen and in the unforgiving light of day. Buneau’s inexperience playing monsters is obvious in his lumbering performance, while the mechanical head looks just that: clunky and, at times, faintly ridiculous.

Quite rightly, Barker disassociated himself from both Underworld and Rawhead Rex. There was no more contact between himself and George Pavlou and Green Man unknowingly let their options lapse on the other four stories from Books of Blood. This didn’t stop them trying to develop another couple of projects based on the tales, but Barker involved his lawyers and the producers soon backed down.

Rawhead Rex as depicted by artist Les Edwards was much closer to the original concept than its cinematic counterpart (courtesy Les Edwards).

It is interesting, though, that without these experiences he wouldn’t have had the major impetus to direct. If they had taught him one thing it was this: To see a satisfactory adaptation of his work, he’d have to make one himself. And it is ironic that a line David Dukes utters in Rawhead should show him the way. “Go to Hell,” he says. “Just go right to Hell!”

In the same 1986 interview with Fangoria, Barker also stated: “I want to direct. I directed in theatre, and I like working with actors, I like community projects. So, we’re putting a project together from a novella I wrote called ‘The Hellbound Heart.’ ... I did a screenplay from it which I hope to be directing this year. We’re going to call the movie Hellraiser.”15 Obviously the author would find film directing a little different from plays, but his theater experiences still stood him in good stead. It is at this point that we must also consider the art house shorts he shot in the 1970s, made with many of those same f

riends. Actually, Barker’s first films were naive experiments with a friend from his early teens, Phil Rimmer. He’d already written short plays with Rimmer—Voodoo & Inferno (1967)—about crazed Germans and, naturally, Hell. Then they progressed on to stop-motion efforts with a Super 8 millimeter camera influenced greatly by Barker’s hero, effects man Ray Harryhausen. One of these involved an Action Man (the UK equivalent of a G.I. Joe doll), some plasticine and lots of worms from the garden. The setting was a slime-covered graveyard constructed in Barker’s bedroom and the directors held lamps close enough to make the scenery bubble.

In 1973, the pair made a version of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, itself a biblical tale which recounts another bargain. The legend of Salome revolves around King Herod’s stepdaughter, who falls in love with the pious Jokanaan (John the Baptist) but is rejected. In exchange for his severed head, she dances for Herod. The group filmed on 8mm stock in the cellar of a florist’s shop in Liverpool. They had a single handheld light and the sets were wallpaper turned over with patterns painted on it. Anne Taylor took the title role, while Doug Bradley—who had played a blind Jokanaan in a previous stage version—was granted his first cinematic encounter with make-up, playing King Herod. The whole thing was developed in Rimmer’s house, then edited by hand.

Pain Cages

Pain Cages Nailbiters

Nailbiters The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy

The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy